The human brain still distinguishes itself from the most advanced artificial neural networks by its ability to radically generalize—to extrapolate far beyond the training distribution, in such a way that requires not just surface correlations but deeper understanding. This remarkable ability relies on the discovery of symmetries—forms of structure that remain invariant under transformation—one of the simplest and most fundamental examples of which is found in base addition.

Using base addition as a case study, my bachelor’s thesis at Princeton was an investigation of the inductive biases of artificial neural networks. We found that, if taught to add using the right symmetries, even simple recurrent networks (RNNs) can achieve radical generalization, and that learnability is closely correlated with the symmetry used. I’m proud of and much enjoyed this project, enough so that this past year my collaborators and I refactored it into a paper which we’ve submitted for publication (currently under review; see preprint).

Though our paper probes at how symmetries enable radical generalization, it did not seek to answer a fundamental question: what does it even mean for a neural network to “use a symmetry”? That is, to the extent that a neural network makes use of a symmetry, how is that symmetry represented and computed internally? In this post, I hope to make progress towards answering that question in the case of RNNs learning base addition; in particular, I find that RNNs represent numbers along a helix at both the beginning and end of their computation.

1. Related Work

There is a fascinating area of research studying the representations of artificial neural networks, particularly in large language models (LLMs)—examples of LLM representations are as varied as refusal (Arditi et al., 2024), days of the week (Engels et al., 2025), and even truth (Marks & Tegmark, 2024). Inspirational to this project was a recent paper finding that LLMs represent the numbers 0-99 along a helix (Kantamneni et al., 2025). Similarly, research has found that even small transformers represent numbers using a Fourier basis for numeric tasks such as modular addition (Nanda et al., 2023) and multiplication (Bai et al., 2025). In a more general framework, it appears that transformers use group representations to compute finite group composition (Chughtai et al., 2023).

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Training RNNs on Base Addition

The problem of base addition in base $b$ is formulated as follows: Two multi-digit numbers are constructed as $n = (n_k, …, n_1)$ and $m = (m_k, …, m_1)$, composed of lists of $b$-dimensional one-hot-encoded digits ($n_i$ and $m_i$) ordered from most ($k$) to least (1) significant. As input, one digit from each number is presented, in this case from least to most significant, with special tokens denoting the (heldout) digits of the answer sequence $s = (s_k, …, s_1)$. That is, the input sequence input $X$ is

\[X = (n_1, m_1, *, ..., n_k, m_k, *).\]For the purposes of this small study, I focus on the bases $b \in [3:10]$ and the standard carry function—see my preprint and Section 4.2 for discussion of carry functions.

For base $b$, the model is comprised of a single-layer RNN (viz., Elman Net) with input and hidden dimensions of $b$ and $4b$, respectively, followed by a linear layer with input and output dimensions of $4b$ and $b$, respectively. A separate model for each base was trained to add 3-digit numbers, using the cross-entropy between the output logits and the answer sequence as the loss. Training progressed over 5,000 epochs over all 3-digit tuples ($n, m$), with a batch size of 32 and a learning rate of 0.005 using the Adam optimizer. After training, the models were evaluated on a subset of 6-digit numbers, all achieving $\sim 1.0$ testing accuracy.

2.2. Helix Fitting Procedure

For each model, I extracted the RNN embeddings $X_e \in \mathbb{R}^{b \times 4b}$ (note that these are given by the learned embedding matrix that linearly encodes the one-hot digits to the hidden space). As helical basis, I constructed $H \in \mathbb{R}^{b \times 3}$ with rows $[\cos(t_k), \sin(t_k), t_k]$, where $t_k = 2 \pi k / b$ for $k \in [b]$, and then fitted $H$ to the embeddings with least-squares, finding $B \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times 4b}$ such that $X_e \approx H B$. An identical procedure was followed for the unembeddings $X_u \in \mathbb{R}^{b \times 4b}$ (these are given by the learned unembedding matrix that linearly decodes the logits from the hidden space).

3. Experiments

3.1. Helical Embeddings and Unembeddings

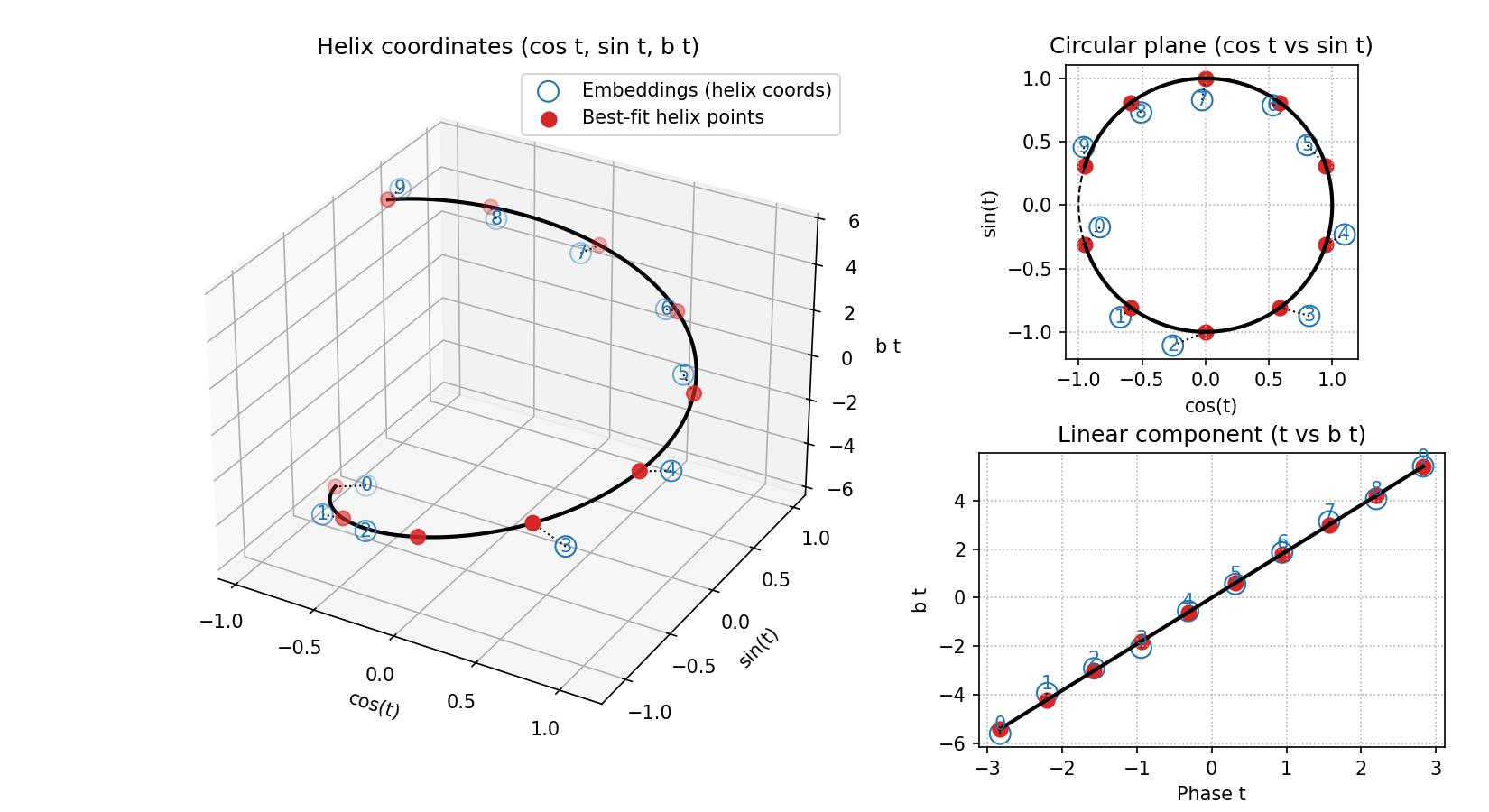

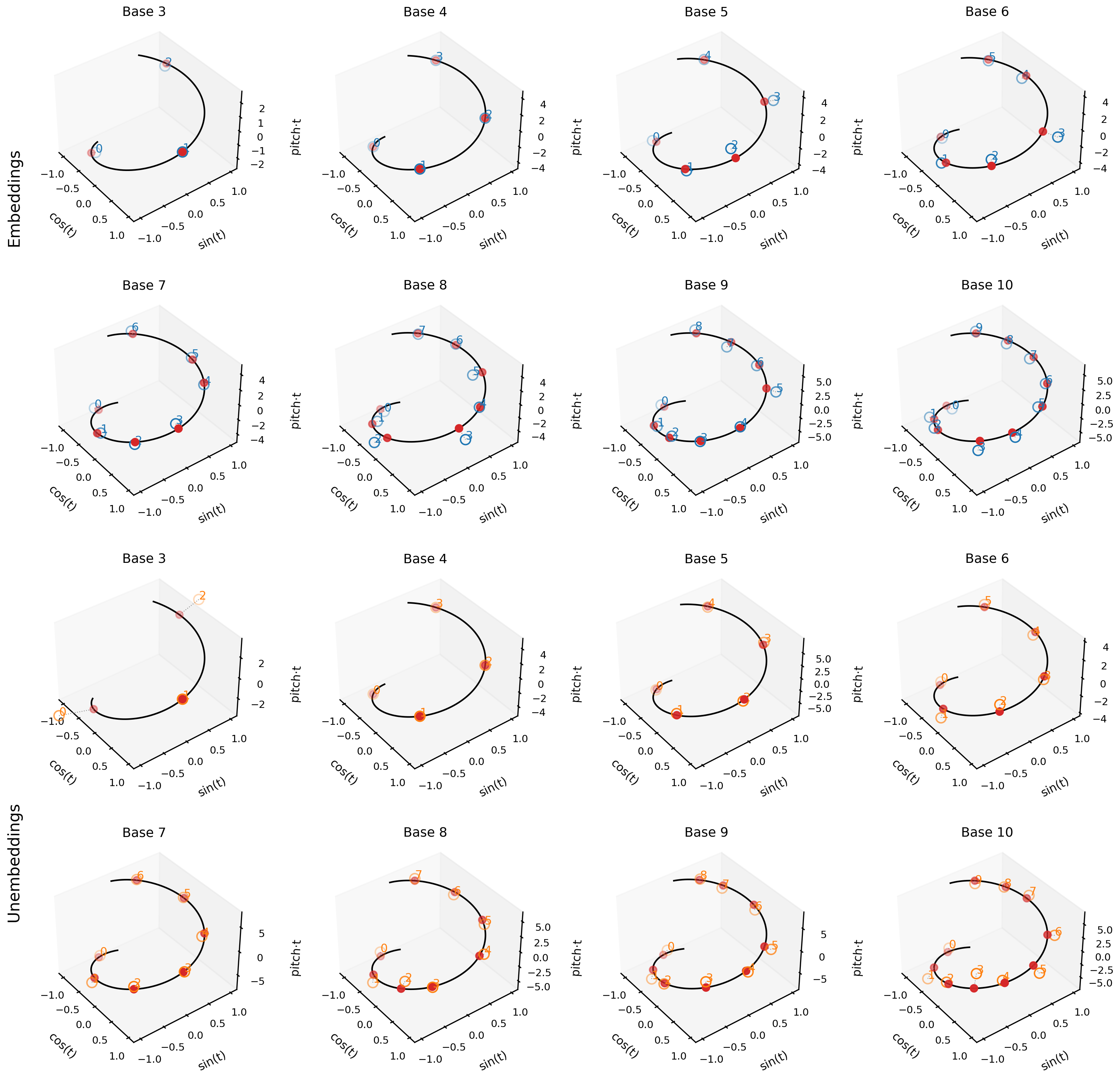

After training and fitting as described in Section 2 for bases 3 to 10, I evaluated the quality of the helical fits for the embeddings and unembeddings. First, isolating a representative example, the figure below shows the helix fit for the base 10 embeddings—note its high quality, with $\text{RMSE} = 0.214$ and $R^2 = 0.883$. The other helical fits are shown below; they are all visually convincing.

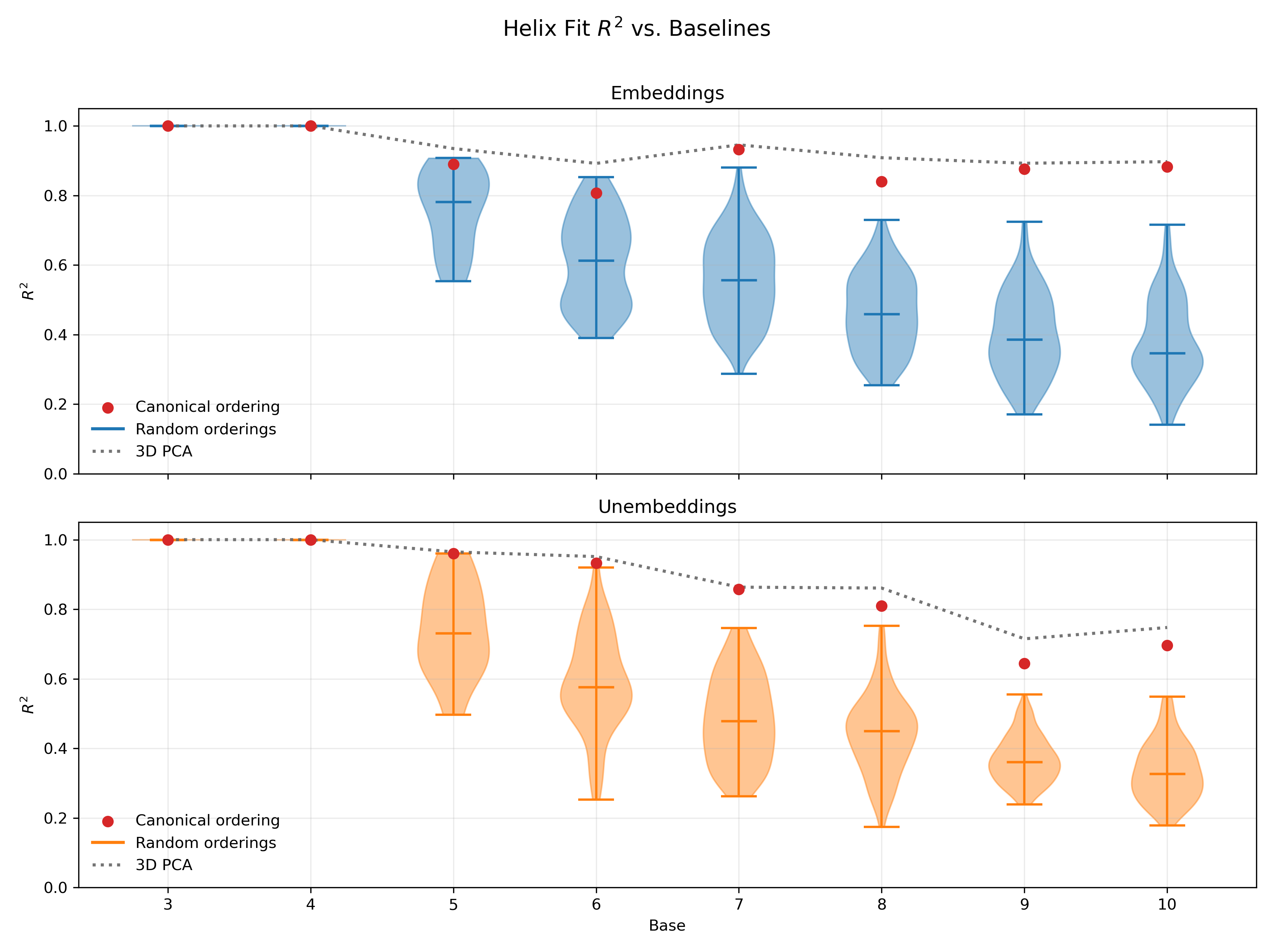

3.2. Quality of Helix Fits

To quantitatively assess the quality of the helix fits, I compared to two baselines: (i) the first 3 principle components, which is a strong baseline given that the helix is a 1-dimensional manifold; and (ii) helix fits using random orderings (e.g., 0, 2, 1 for base 3), which probes the expressivity of the helix regardless of whether the ordering of digits along it is relevant to the network’s computation. Across most bases, the helix in the canonical ordering (i.e., the proper ordering with this carry function; see Section 4.2 for more detail) separates itself above the randomly-ordered helices, and in many cases approaches (or nearly matches) the 3D PCA baseline.

4. Discussion

4.1. RNNs Add Using a Helix

From the helix figures as well as the $R^2$ analysis, we can see that—for the most part—the helices provide an impressively good fit to not only the embeddings, but also the unembeddings. Together, this provides suggestive evidence that helical structure is important from beginning to end in the model’s computation. This mirrors recent work number helices in LLMs (see Section 1). Corroborated across architectures and even at model sizes this small, these findings suggests that helical structure may be the most compact representation of base addition with multiple digits—future work might study group representations of the group multi-digit base representation worked out in my thesis.

4.2. Future Directions

There are a variety of future directions from this very preliminary first study, which I intend to follow-up on in the posts to come.

-

Extend to other carry functions: In my thesis, I use group cohomology to formally construct base addition, and in the process reveal many alternative ways of carrying. This provides the setup for the rest of the paper, which analyzes inductive biases of neural networks in terms of the complexity of different carry functions. In this post, I just focus on the standard carry, but I intend to replicate this for other carry functions in bases 3 to 10. If they too display helices according to their particular systems, this provides further evidence that the helices are causally relevant to computation.

-

Causal analysis: Going beyond representation to causation is an important step in interpretability, and it would be interesting to do so here as well—activation patching of the helix embeddings would be a first-step to look into. In particular, this might help to isolate how carrying from is represented—e.g., by ablating along the helix’s linear component.